Goldilocks Would Love Incident Command

In the past month, I’ve heard three different iterations of the same story: a competent hospital emergency manager has discussed how his/her hospital is reluctant to initiate incident command even when faced with the need for additional resources; how they try to implement something called “ICS Light” as a way to deal with less-than-catastrophic situations. I believe this is the result of three different phenomena:- The lack of unambiguous triggers to initiate action. Is 20 people in the Emergency Department (ED) waiting room enough to trigger the alarm? 50? 25 patients, but three of them have cardiac symptoms? Make it easy for your staff to initiate an incident. This gives them cover for asking for help – something many very competent people struggle with. Requiring staff to “declare an incident” at certain thresholds ensures consistency and relieves staff of the decision-making process. It also helps overall situational analysis. A minor incident in the ED might be connected to a minor incident elsewhere in the hospital, but unless the Emergency Manager (EM) is informed about both, nobody can make that connection.

- The lack of comfort with ICS. People avoid what’s uncomfortable. They’d rather struggle with what’s comfortable, even if it isn’t working (no, we’re not talking about marriages here; that’s outside my scope). The solution is to use ICS frequently enough that people get comfortable with it. ICS should be used at every incident (at the level appropriate for that incident), for special and planned events, and for exercises.

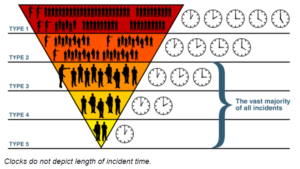

- A lack of appreciation for the modular organization management characteristic of ICS. ICS is not an all-or-nothing process.

The incident typing discussed in IS-200 and used throughout the wildland fire service can be compared to the “alarm” systems used in towns and cities. When someone calls 9-1-1 and reports a fire, the typical response is a few pieces of apparatus and a chief officer in that area. In most of those alarms, the office of the first arriving apparatus can manage the response with the resources assigned, and the chief officer returns to being available for other calls. If, however, smoke is belching from many windows, the initial IC can request a “second alarm.” This not only results in more engine and truck companies being dispatched, but it also assigns resources to handle theexpected command and general staff responsibilities that will be managed at the scene: safety, someone to liaise with utilities and other agencies, and various operations section units. A third alarm will increase the assignment of these staff resources still further.

Your hospital (or large nursing home or seniors community) should consider similar scaling of response. Anytime a department’s needs exceed its resources, an incident can be declared, and administration monitors the incident, even if no additional resources are required. If the incident grows in scope, or if additional incidents around the facility begin to tax resources, then it can step up the incident management staff based on need.

You should realize that incident management must grow based on scope (size), complexity, and duration. Once an incident grows to require type 3 incident management, outside resources probably will be required. It’s important to know what incident management resources are available at the local and regional level. These regional incident management teams may not have healthcare incident management experience. That’s why you should consider meeting them, sharing your incident management capabilities and needs, and include them in your exercises, so that they can better serve you when the fertilizer hits the ventilator in large quantities.

For smaller incidents – the vast majority of incidents you will experience – you should establish the leanest, most efficient incident management team that will handle the problem. That could well be one person, along with some operational resources. That team may grow during the incident, then shrink when the operations allow. The objectives of the incident, and the principle of span of control, dictate the size of the planning team.

This is why Goldilocks would love ICS. It’s never too big or too small. It should always be “just right” for each incident.

The incident typing discussed in IS-200 and used throughout the wildland fire service can be compared to the “alarm” systems used in towns and cities. When someone calls 9-1-1 and reports a fire, the typical response is a few pieces of apparatus and a chief officer in that area. In most of those alarms, the office of the first arriving apparatus can manage the response with the resources assigned, and the chief officer returns to being available for other calls. If, however, smoke is belching from many windows, the initial IC can request a “second alarm.” This not only results in more engine and truck companies being dispatched, but it also assigns resources to handle theexpected command and general staff responsibilities that will be managed at the scene: safety, someone to liaise with utilities and other agencies, and various operations section units. A third alarm will increase the assignment of these staff resources still further.

Your hospital (or large nursing home or seniors community) should consider similar scaling of response. Anytime a department’s needs exceed its resources, an incident can be declared, and administration monitors the incident, even if no additional resources are required. If the incident grows in scope, or if additional incidents around the facility begin to tax resources, then it can step up the incident management staff based on need.

You should realize that incident management must grow based on scope (size), complexity, and duration. Once an incident grows to require type 3 incident management, outside resources probably will be required. It’s important to know what incident management resources are available at the local and regional level. These regional incident management teams may not have healthcare incident management experience. That’s why you should consider meeting them, sharing your incident management capabilities and needs, and include them in your exercises, so that they can better serve you when the fertilizer hits the ventilator in large quantities.

For smaller incidents – the vast majority of incidents you will experience – you should establish the leanest, most efficient incident management team that will handle the problem. That could well be one person, along with some operational resources. That team may grow during the incident, then shrink when the operations allow. The objectives of the incident, and the principle of span of control, dictate the size of the planning team.

This is why Goldilocks would love ICS. It’s never too big or too small. It should always be “just right” for each incident.